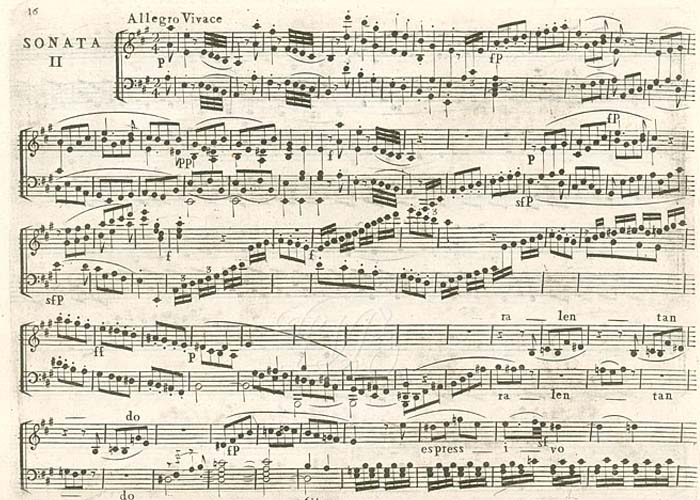

Piano Sonata #2 in A Major Opus 2 #2. It's part of the Op. 2 sonatas composed in 1795 and dedicated to Joseph Haydn.

"The genie is made up of 2% talent and 98% constant perseverance." –L. V. Beethoven.

Info and RegistrationThe overall view of Sonata No. 2 is that it is agile, graceful, and lyrical. This contradicts its radical and revolutionary tendencies, also its enormous technical difficulty. Beethoven was determined to surpass his predecessors from the start, and this sonata is already well beyond Mozart and Haydn.

A striking aspect of this sonata is its style with the tone: it changes unexpectedly and often with an extremely modern sound; see what happens in the second thematic group of the first movement, where it moves in intervals of a minor third, the use of C and F major in the development of the movement, B flat in the second, G# minor in the third and F with B flat major in the last section of the 4th movement. It's amazing that something so elegant moves with such modulating aggressiveness, and the color that Beethoven generates with these kinds of changes explains why the romantics couldn't get enough modulations in the sevenths, sixths or thirds.

There are the textures that Beethoven uses throughout the sonata that were previously unknown in piano literature. In the 1st movement, parodic extensions of melodic forms of rise and fall so common in the classical period, with intense red-hot scales, as well as some sublime 3-part textures. In the second movement, beautiful Brahmsian textures and pizzicato in the lower registers against sustained midtones. In the fourth movement an operatic jump down, absurd, but that's what makes it great, along with a deliberately over-involved imitation of a motif taken from the first movement: an ascending arpeggio.

It is important to note that the defining characteristics of Beethoven's style already abound: lots of motivating and intelligent manipulation in the first movement and by classical standards, an unusually long movement. This opens the door to the big movements that happen in music from then on.

The third movement, changes from minuet and trio to scherzo. The tempo is faster and the spirit is more playful, but the structure and time signature remain the same. The movements tend to lengthen, especially the first movements, where the exhibition incorporates multiple ideas of development. Longer codas in the second and fourth movement. The movements introduce modulation away from the starting pitch and the use of previous thematic material.

More daring harmonic relationships are presented. The second theme in the exposition of the first movement comes in E minor, the minor parallel of the expected major major. In the Sonata No. 1, Beethoven simply mocked the listener with accidentals suggesting the minor parallel of the expected key, but here he goes all the way. The introduction of unexpected tones occurs in the codas to the 2nd and 4th movements.

Three movements open with tonic or dominant arpeggios and scale fragments: the first movement, measures 1-10 and so on; third movement, measures 1-8, and so on; fourth movement, bars 1-4, and so on, and also 100, 104, 112.

The opening phrases of the third and fourth movements rise to the same Mi.

The exposition is expanded with the introduction of three ideas in the first subject area, a second thematic modulator in the dominant minor, and then an extended section in the expected major dominant that refers to the material of the first subject.

The opening segment of the first theme is a Mannheim Opening, presenting the figuration in octaves.

The second segment of the first track is an ascending scale in staccato eighth notes with a closing cadence written with voice levels. Its repetition exhibits invertible counterpoint.

The third segment of the first song opens with ascending triplets of sixteenth notes, posing a challenging technique. Beethoven frequently places technical challenges near the beginnings of sonatas: the double thirds in the first three bars of the Sonata No. 3; broken sixths in bars 11-15 of Sonata No. 7; the fast notes in bars 3 to 18 of Sonata No. 17; the broken arpeggios of bars 14 and 15 of Appassionata; and the double notes of bars 29 to 33 of the Sonata No. 26. This segment opens on the tonic but modulates to the dominant of E major, the expected key of the second subject area. The introduction of the descending sixth in C at measure 49 prepares the unexpected key of the second E minor theme.

Entering into E minor, the second theme is development, ascending to G major, B♭ major, and a series of sounds in diminished sevenths until reaching the climax in measure 76 with the return of the first segment of the first theme, now outlining a seventh diminished harmony that acts as VII7 resolving in E major.

An extension of the second subject area in the expected key of E major opens with a broken eighth figuration. The third segment of the opening theme returns at measure 92 and extends to close the exhibition.

Fingering for the right-hand triplet figures at bars 84 and 85 are shown in the first edition as 1-5-1, 2- 5- 1, 2- 5- 2, 1- 5- 1, 2- 5 - 1, 2- 5- 2, 1- 5- 1, and in 88 and 89 as 1- 5- 1, 2- 5- 2, 1- 5- 1, 2- 5- 1, 2- 5- 2 , 1- 5- 1, 2- 5- 1. This fingering was possible with the light weight of the keys on Viennese pianos, but most artists will find it impractical with today's pianos, instead using both hands to touch the figuration.

There is a dispute over the silence indicated in measure 117. The first edition shows the number 2 in the measure of silence. Having two measures of silence interrupts the grouping of four measures, so some editors believe that one measure of silence is correct and thus indicate only one. Here we assume two measures of silence.

The first segment of the first theme opens in C major and moves through progressions in A ♭ major and F minor, reaching a rest with a chord marked with a fermata in the dominant of F minor. Note the articulation pattern of staccato and non-staccato in this section. For example, compare the downbeats of bars 123 and 125 with those of bars 124, 126, and 131.

Opening in F major, the second segment of the first theme serves as a reminder of the development of the section. Being fragmented up to bar 182, a point at which ornamental notes and melodic notes require quick jumps of the interval of a tenth, a technical challenge.

In the first edition, the upper voice in the right hand of the previous bar shows the four eighth notes as G♯, but the last bar presents the four notes as G♯, A, B, and G♯. Some editors believe the bars should match, others praise the variation.

All the material of the exhibition is presented in order, the second thematic area entering the minor parallel of the tonic at measure 278 and evolving to the starting key at measure 304. The beginning of the recapitulation is marked forte , in contrast to the piano in the exhibition.

A short but interesting turnaround affirms a phrase in E major in bars 242 to 244, then lowers it a full key to D major in bars 245 to 248, a progression used later and with more daring in the openings of the Sonata No. 16, and the Sonata No. 21.

There is no coda.

This is the first slow movement with the expressive goal of creating a contemplative mood, rather than presenting melodies that flow through singing. Later examples of this type of movement occur in the sonatas 3, 4, < a href="sonata-5.php">5, 7, 17, 21, 26, 28, 29, 30, 31 and 32.

The texture of the main theme suggests that of a string quartet, the lower part is written in sixteenth notes staccato, imitating pizzicato. Other examples of this texture on the piano can be seen in Sonata No. 4, second movement in the middle section; Sonata No. 15, second movement on the opening theme; Sonata No. 18, also in the opening theme the second movement.

The harmonic progression to the Neapolitan sixth at bar 26 is interesting. There is a relationship between this passage and the progressions in the third movement of the Sonata No. 29 in measures 14 to 15, 22 to 23 and so on. The progressions in both sonatas range from F minor to Neapolitan sixth.

An coda is introduced with the typical purpose of bringing the movement to a quiet close.

A second coda enters fortíssimo at the unexpected minor parallel, D, passing through B♭ major in bars 61 to 63 before resolving at the opening pitch. This added section is the first example in piano sonatas of extending the ending using development techniques. This idea grows throughout the sonatas periodically and reaches its peak in codas like those that attend the first movements of the Sonata No. 21 and the Sonata No. 23.

A variation of the main theme returns to the opening tone, bringing the movement to a quiet close.

The concept of the light and cheerful scherzo is married to the traditional structure of the traditional minuet and trio in sonatas. The scherzo and trio sections feature full returns of their eight-bar opening segments. The trio is in A minor.

The left hand fingering appears in the first edition, the first and third sixteenth notes as 3-1, an awkward pattern to be used on today's pianos.

The first edition shows sforzandi in the first beat of bars 64 and 65. Many editors believe that the mark at 65 is a mistake and move it to bar 66, thus preserving a sforzandi pattern in alternate bars in the passage.

This is the first occurrence in sonatas of a rondo type that is related to the Sonata-Allegro Form in which the first section B is in the dominant and the second is in the tonic. This structure appears throughout the piano sonatas with various alterations that bring it even closer to the sonata-allegro concept, such as including development in the C section or eliminating the final return of A. Examples of its use in sonatas are the Sonatas 2, 3, 4, 8, 9, 11, 12, 13, 15, 16, 21, 25 and 27.

The C section of this rondo is issued in two parts, the first part marked to be repeated and the second with the repetition written to effect dynamic and articulation changes, as well as the transition back to the A section. The second section recapitulates much of the first section in its closing.

The rhythm throughout the C section features triplet eighth notes in one hand with a dotted eighth followed by a sixteenth note in the other. By the date of this sonata, in early Baroque the practice of lining up the sixteenth note with the third note of the triplet had gradually eroded in favor of separating the sixteenth note from the triplet. - Treaties of J. J. Quantz (1752), M. Agricola (1765) and D. G. Türk (1789) recommending separation.

The coda reflects the procedure used at the end of the second movement. Here the theme A deviates in B major, and the material in section C returns. With the return to the opening tone, a part of the theme A is rethought and unfolds.