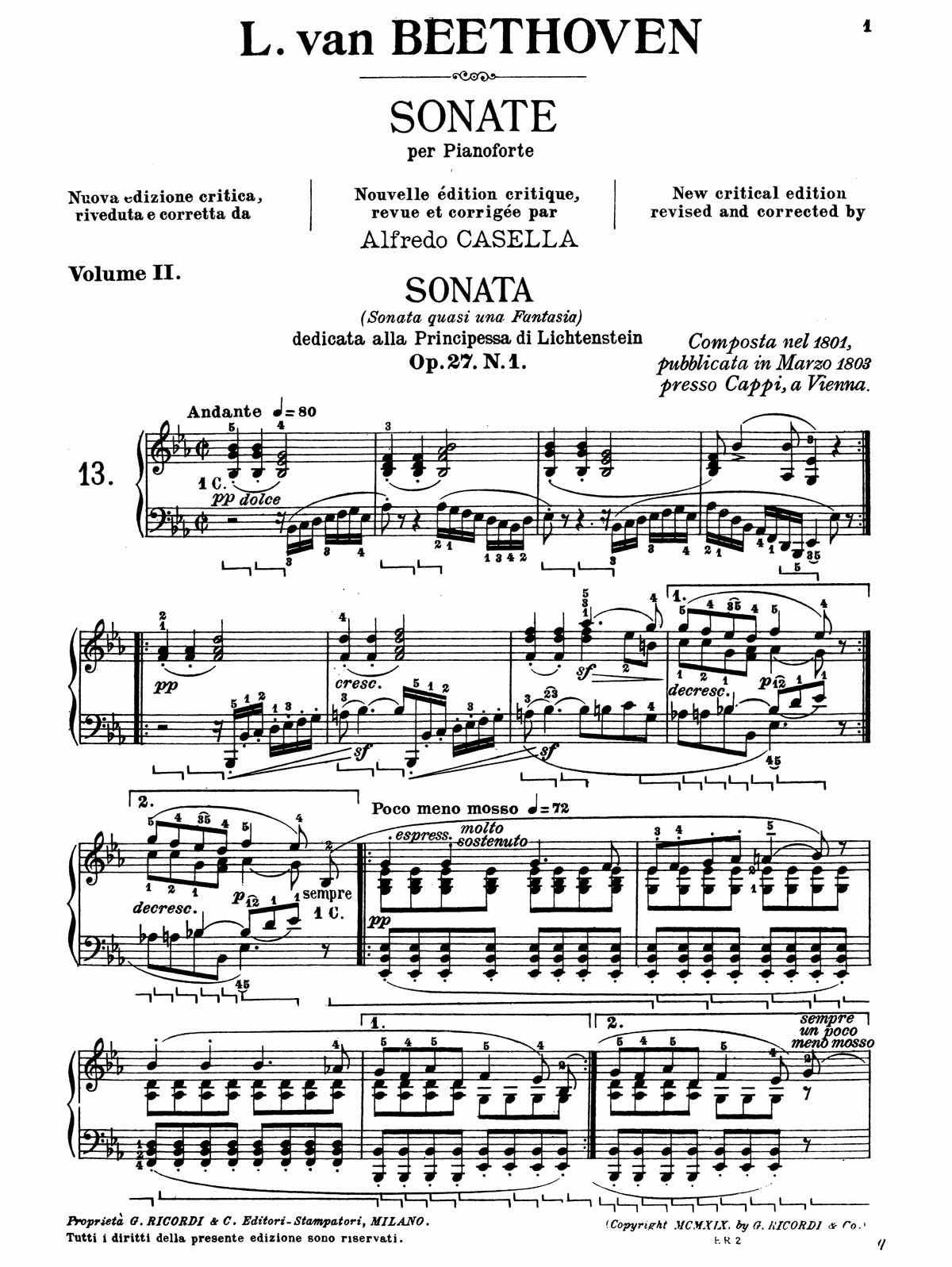

Beethoven Piano Sonata 13

Composed between 1800 and 1801 and is dedicated to the Princess of Liechtenstein.

Like the well-known piano sonata "Claro de Luna", together with which it was published under the same catalog number, this one bears the title "Quasi una Fantasia" (Almost a fantasy). The term refers to the distance between the form and the classical sonata of Mozart and Haydn, it was used by Beethoven with some freedom. While earlier sonatas, such as No. 12, or those from your last period, such as No. 29, also introduced changes in the genre, carried other titles, such as "Große Sonate für das Hammerklavier" (Great Sonata for the Piano).

Music Courses

"The genie is made up of 2% talent and 98% constant perseverance." –L. V. Beethoven.

Info and RegistrationBeethoven Piano Sonata 13 –Interesting Facts

Even by his own gender-breaking standards, Beethoven went through a kind of experimental phase in his sonatas Op.26 and Op. 27, and this, Op.27 No.1, represents the most surprising work of that period. Everyone who has played it loves it, it is a bit dark and does not seem flashy right away. But that's really part of his design, where Beethoven takes the archetypally argumentative form, the sonata, and gives a basically narrative fantasy, improvised, episodic character.

There are no gaps between all the movements, which are arranged in fast-slow-fast-slow order. Motivational connections are rare. Each movement fills an expressive void that the previous one lacks. The first is elegant. The second; restless, ominous. The third; into. The fourth, festive. There is not a single movement in the form of a sonata. Moods are constantly changing.

Beethoven Piano Sonata 13 –Novelties

The first movement begins with an absurdly simple, almost trivial melody. The only thing that undermines its total naivety is the careful articulation that Beethoven indicates and the constant changes in sonority that animate it. Section C is such a ridiculous contrast to this that it almost looks like a new movement, although its C Major harmony has already been wonderfully anticipated.

The second movement is, again, an articulation exercise, with clearly improvised chord sequences and some of Beethoven's most creative textural writing in the return of the scherzo. It's one of those strange movements that can be interpreted in a thousand ways and come out unscathed.

The third movement hardly deserves the name; a single melody in three parts. And yet it returns at the end of the dizzying and already great final movement, a sudden injection of heartfelt sentiment into an artfully forged rondo; the development section is quite impressive, full of orchestral timbres.

Biography of the Sonatas Op. 27

Beethoven's younger brother, Carl (1774–1815), took over the negotiations with the publishers. and was effective in demanding and obtaining maximum prices for the composer's works. Countess Giulietta Guicciardi (1784–1856) began her piano studies with Beethoven in 1801, and an affair ensued. On November 16, 1801, the composer wrote to his friend Franz Gerhard Wegeler: My poor hearing haunted me like a ghost; and I avoided... all of human society. I look like a misanthrope, and yet I am far from it. This change has been brought about by a lovely and dear girl who loves me and whom I love. After two years I am again enjoying some happy moments, and the first time I feel that marriage could bring me happiness. Unfortunately she is not of my class, and at this time, I certainly could not marry, I still have to work on good business matters. In 1803 Giulietta married Count Wenzel Robert Gallenberg (1783–1839), and the couple settled in Italy. Years later, in a book conversation dated February 4, 1823, Beethoven recalled the romance, speaking with Anton Schindler in French, possibly so that the spies would not understand: He was loved by her, and more than she will ever love her husband... and she was looking for me crying, but I rejected her... If I had wanted to give that life the strength of my life, what would have been left for the noblest, the best?

Fact Information

The Op. 27 sonatas (Sonata 13 and 14) were announced together with the Op. 26 (Sonata 12), by Giovanni Cappi on March 3, 1802. Each sonata bears its own dedication.

Observations

Both sonatas, the 13 and 14, carry the description sonata quasi una fantasia. Each has its irregularities, joining the 12 as experimental works.

Information that might be interesting

This work was dedicated to Princess Josephine von Liechtenstein (1775–1848). She was born Countess Josephine Sophie zu Fürstenberg-Wetra and in 1792 married Prince Johann Joseph von Liechtenstein (1760–1836), a well-known art collector and a field marshal in the imperial army. Not much is known of Beethoven's knowledge of the princess apart from a letter dated September 1805, the letter apparently never delivered, in which the composer asks for financial help for his friend and student Ferdinand Ries.

General remarks

As in the Sonata 12, there is no sonata-allegro structure in this work. Beethoven wrote attaca at the end of the first, second and third movements, thus indicating a continuous flow for the sonata. Furthermore, the third movement is linked to the fourth by a cadenza. As in sonata 12, the second movement is scherzo type and the third one serves as a slow movement. At the end of the fourth movement, eight bars from the slow movement return, thus starting the cyclical return for the first time in the sonatas. Perhaps coincidentally, the cyclical return in Symphony no. 5, is also one in which a part of the third movement returns in the final movement. For the first time in the sonatas, the last movement is the longest, becoming the cornerstone of the work, instead of the first movement. Such a change is also clearly seen in 14, 28, 29, 30, 31 and 32.

Possible connections between movements

The first, third and fourth movements open with phrases that place notes of the tonic triad on strong beats. In the first movement the line moves from the fifth degree of the scale to the third, in the third movement, in A♭ major, from the third degree to the root, and in the fourth movement from one bar in the fifth degree to the root. , back to the fifth, with a passing submediant, and then to the third, with ornamental passing tones.

The first and fourth movements feature similar scale patterns as a response to the opening motifs, in the first movement in bars 1–4 and in the fourth in bars 3–4 and 7–8.

The C major section of the first movement features an arpeggio rising to G, bars 39–40. The second movement opens with a broken chord in C minor rising to the same note, measures 1 to 3.

There is a cyclical relationship between the third and fourth movements.

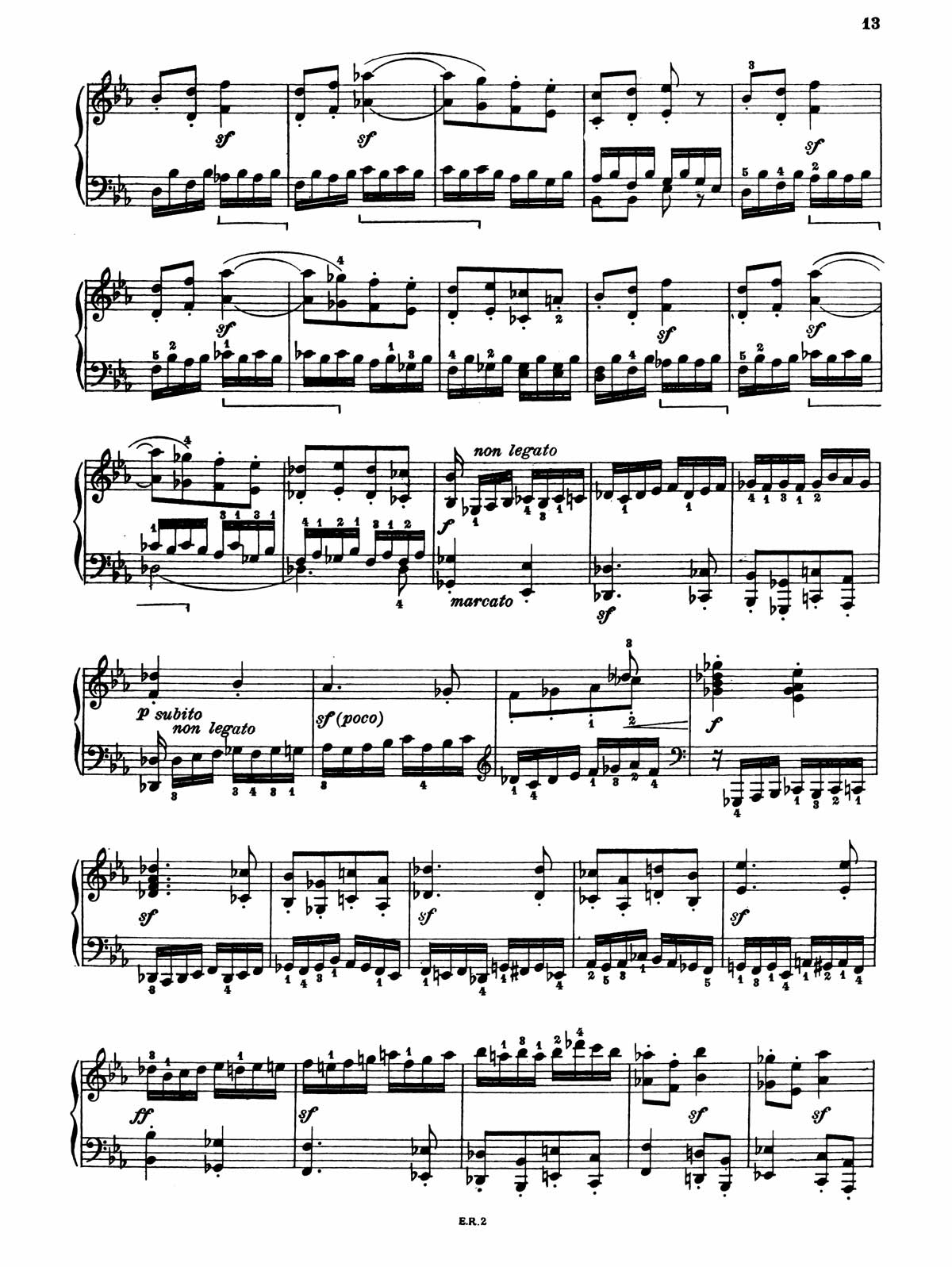

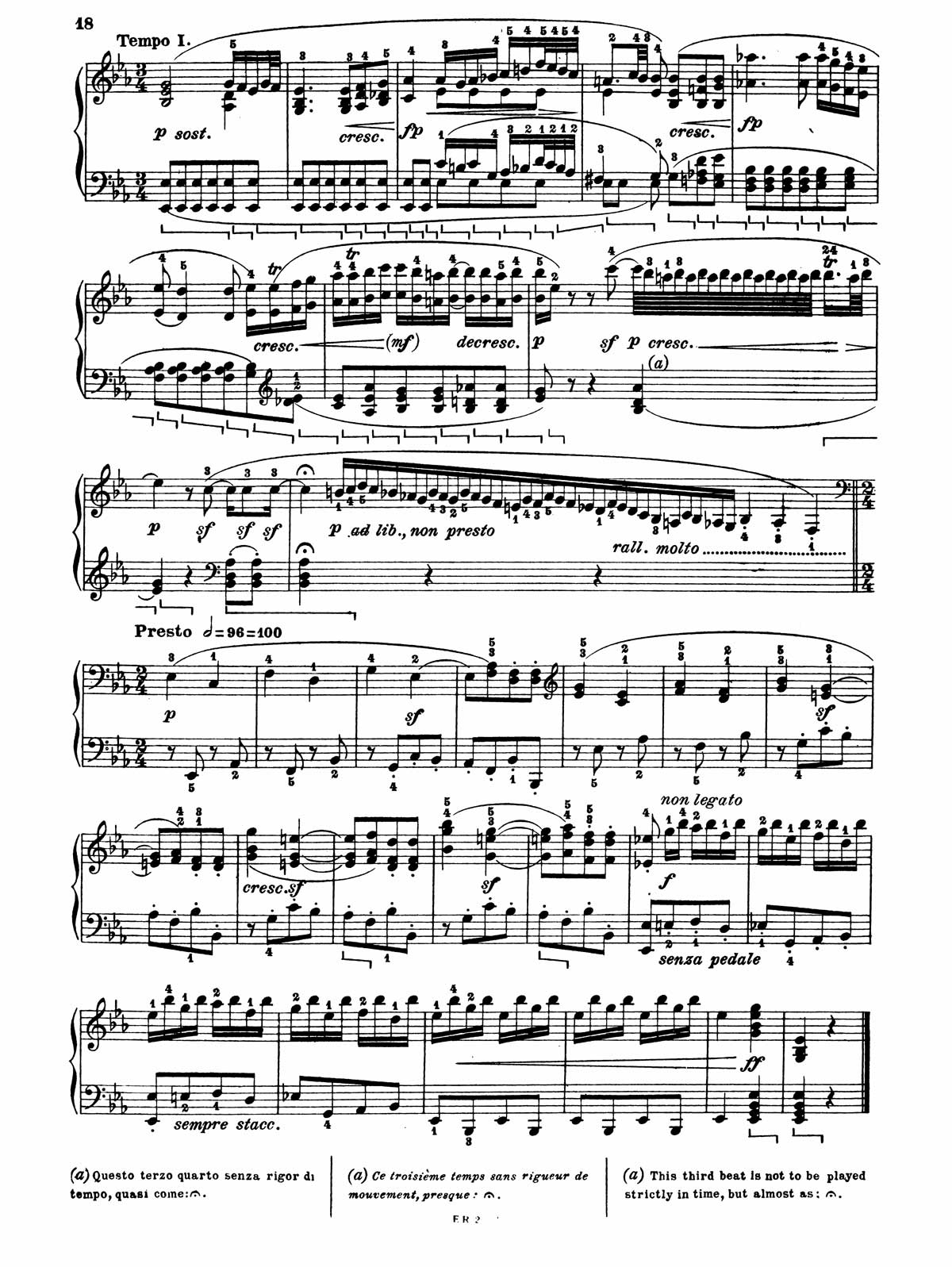

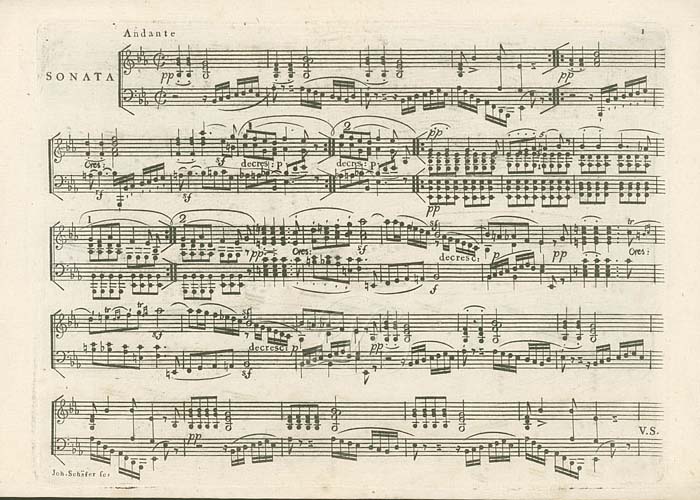

First Movement: E flat major | Andante-Allegro-Andante | 4/4 Alla Breve, 6/8, 4/4 Alla Breve | ABA, Coda

Structure

Sections A and B are subdivided into smaller parts.

Measures 1 to 8

Two sets of four bars in E♭ major are each marked with repeat, the second set with first and second endings.

Measures 9 to 20

A second idea based on the same rhythm is in E♭ major for the first four bars. Then four bars open in C major and modulate back to E♭ major, this passage repeats one octave higher.

Measures 21 to 36

The section returns to the initial set of eight bars, but here the repeats are written to allow for slight variations.

Measures 37 to 62

The contrasting middle section features a key change to C major, a time signature change to 6/8, and a tempo change to Allegro. The first eight bars are marked to be repeated. The repeat for the second group of eight bars is written to include an extended ending that modulates back to E♭ major.

Measures 63 to 78

The opening section returns without written repetitions to effect even more figurative variations.

Measures 79 to 86

A short coda is based on cadences from the dominant seventh to the tonic.

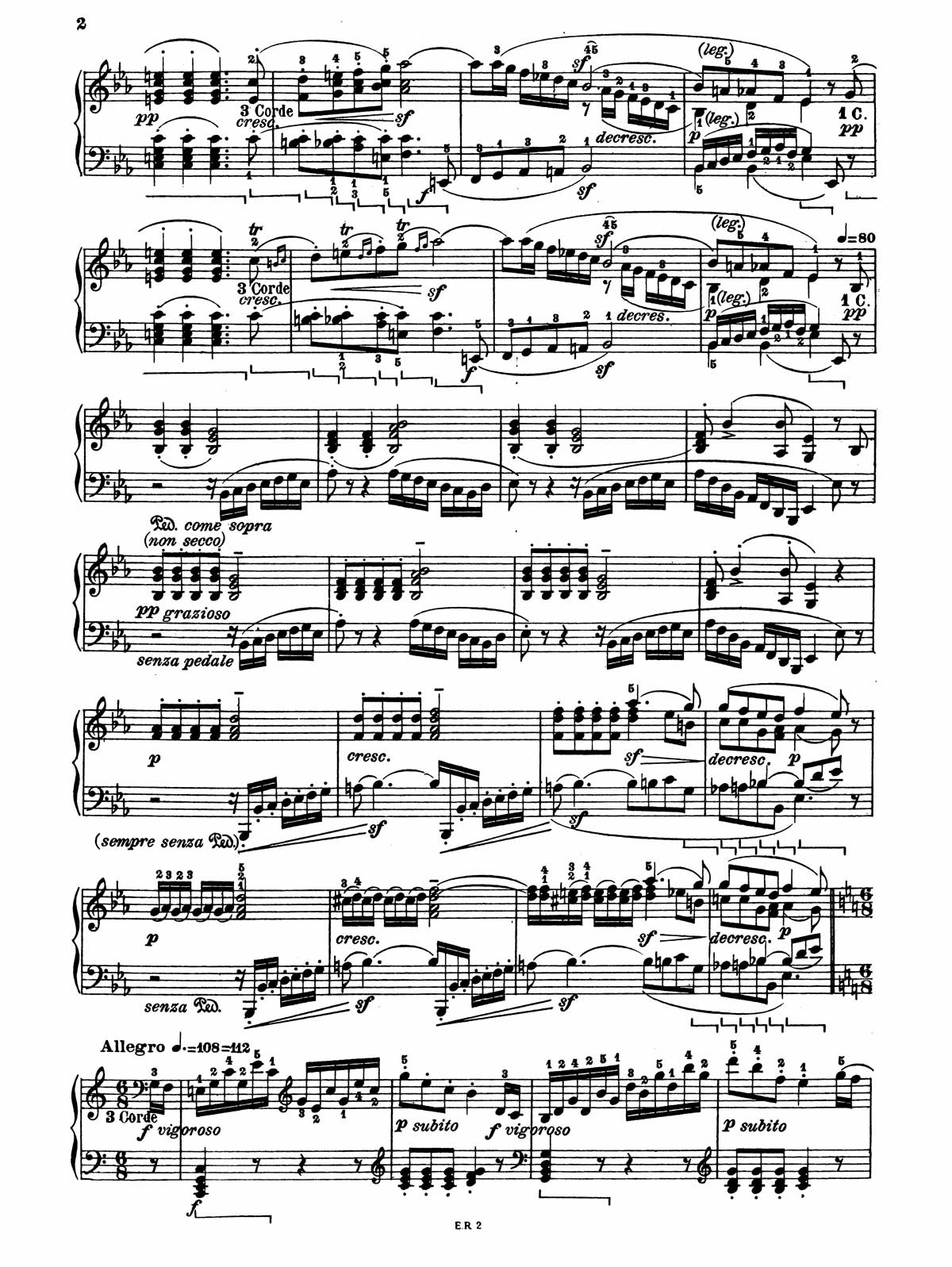

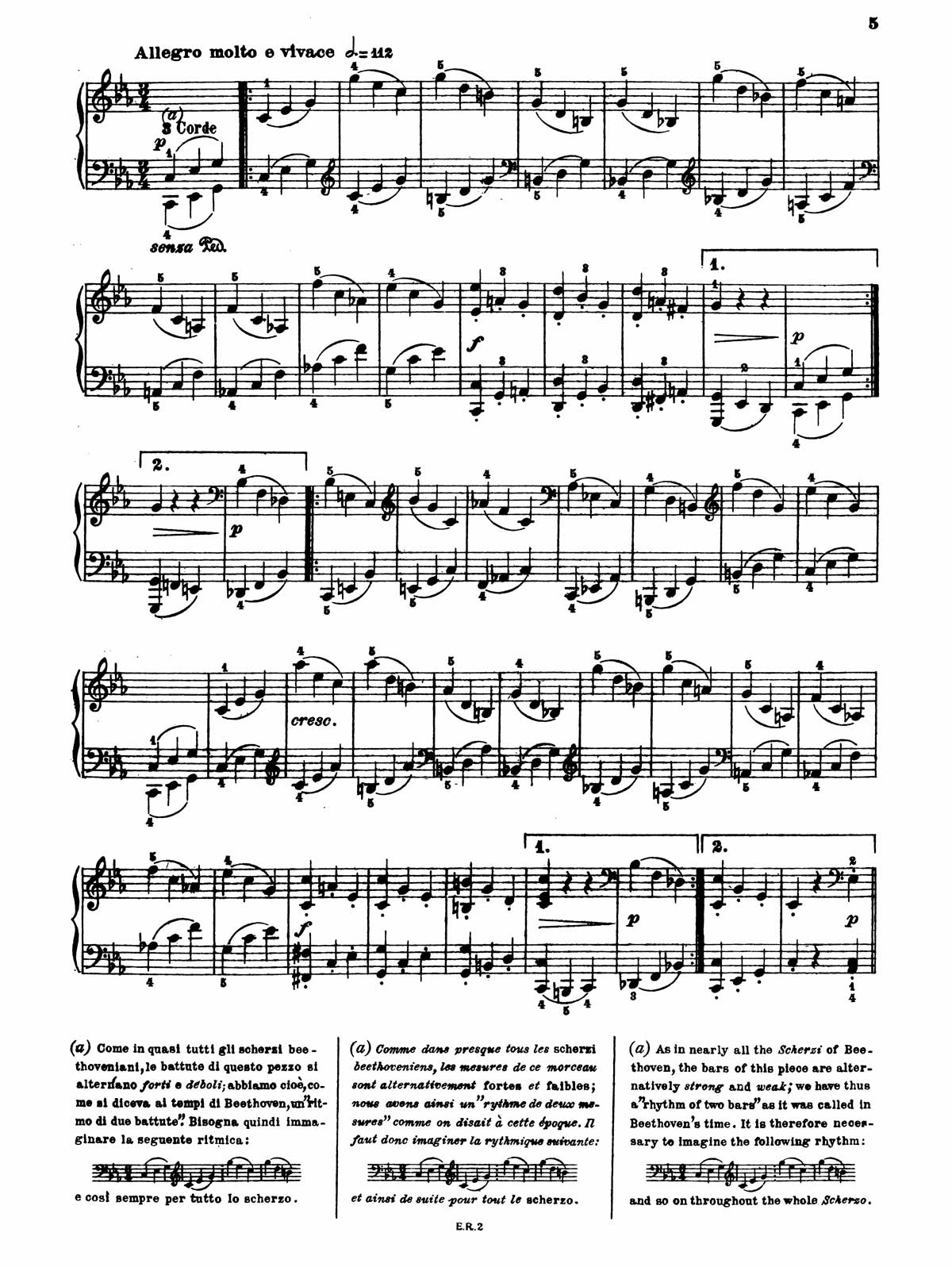

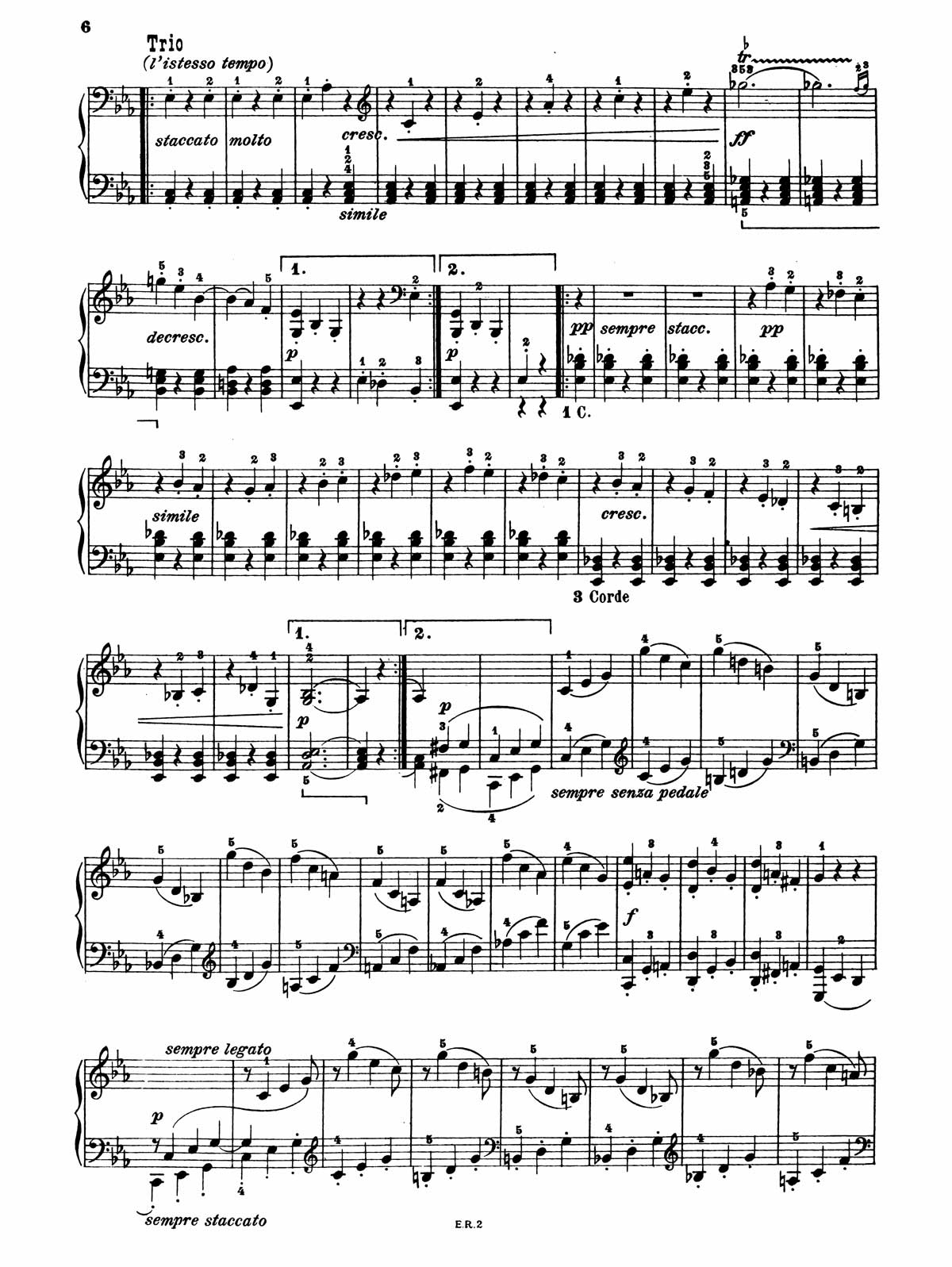

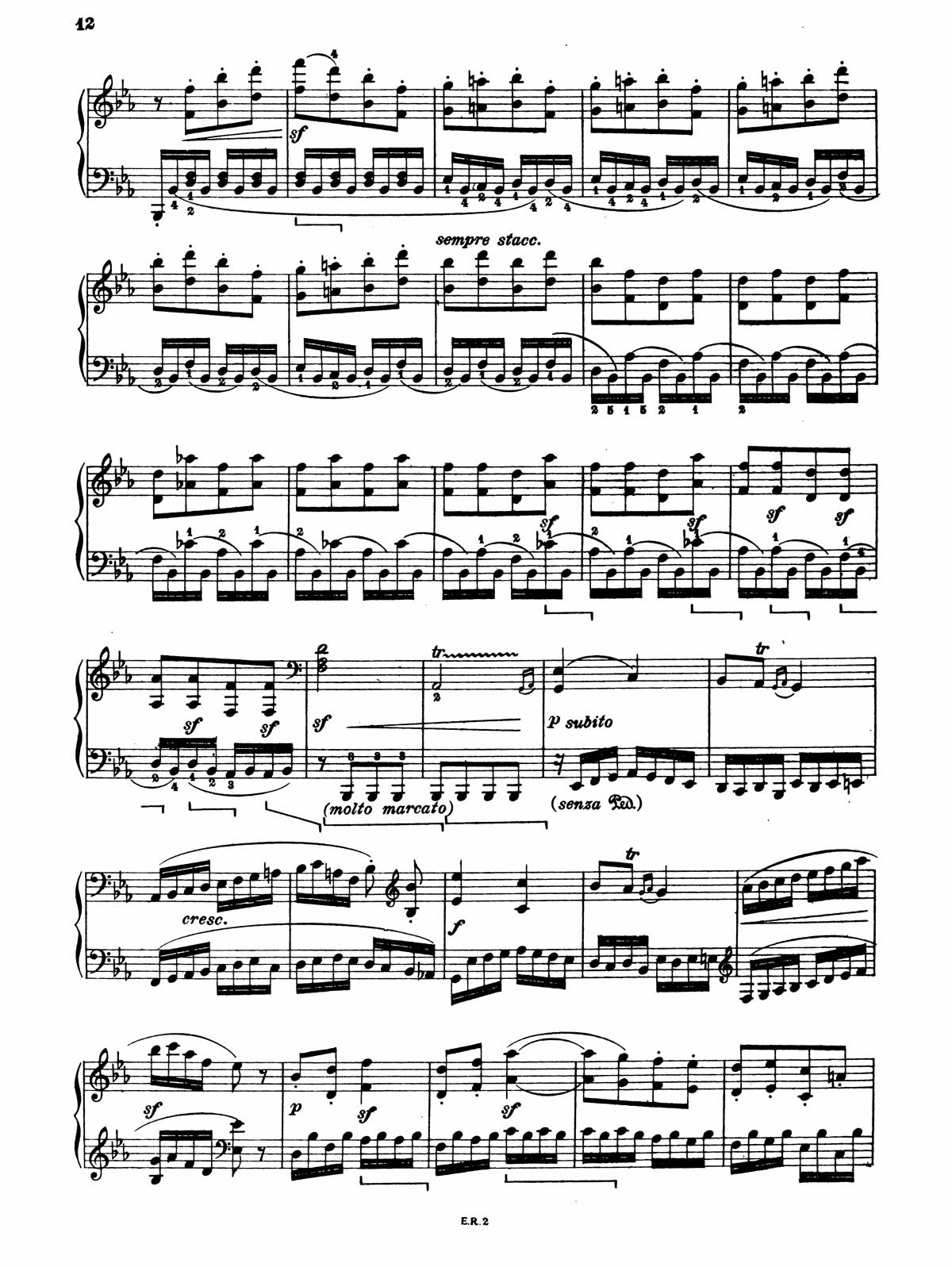

Second Movement: c minor | Allegro molto e vivace | 3/4 | ||:A:||:B:||:C:||:D:|| ||AA′B′|

Structure

This scherzo-like movement is in a modified minuet and trio form, the da capo is written to introduce a syncopated variation of the original exposition in the written repetition of the first part . There is also a twelve-bar extension of the second part with cadences in C major. The first and second finishes attend the sections marked for repeat. Sections C and D are in A♭ major.

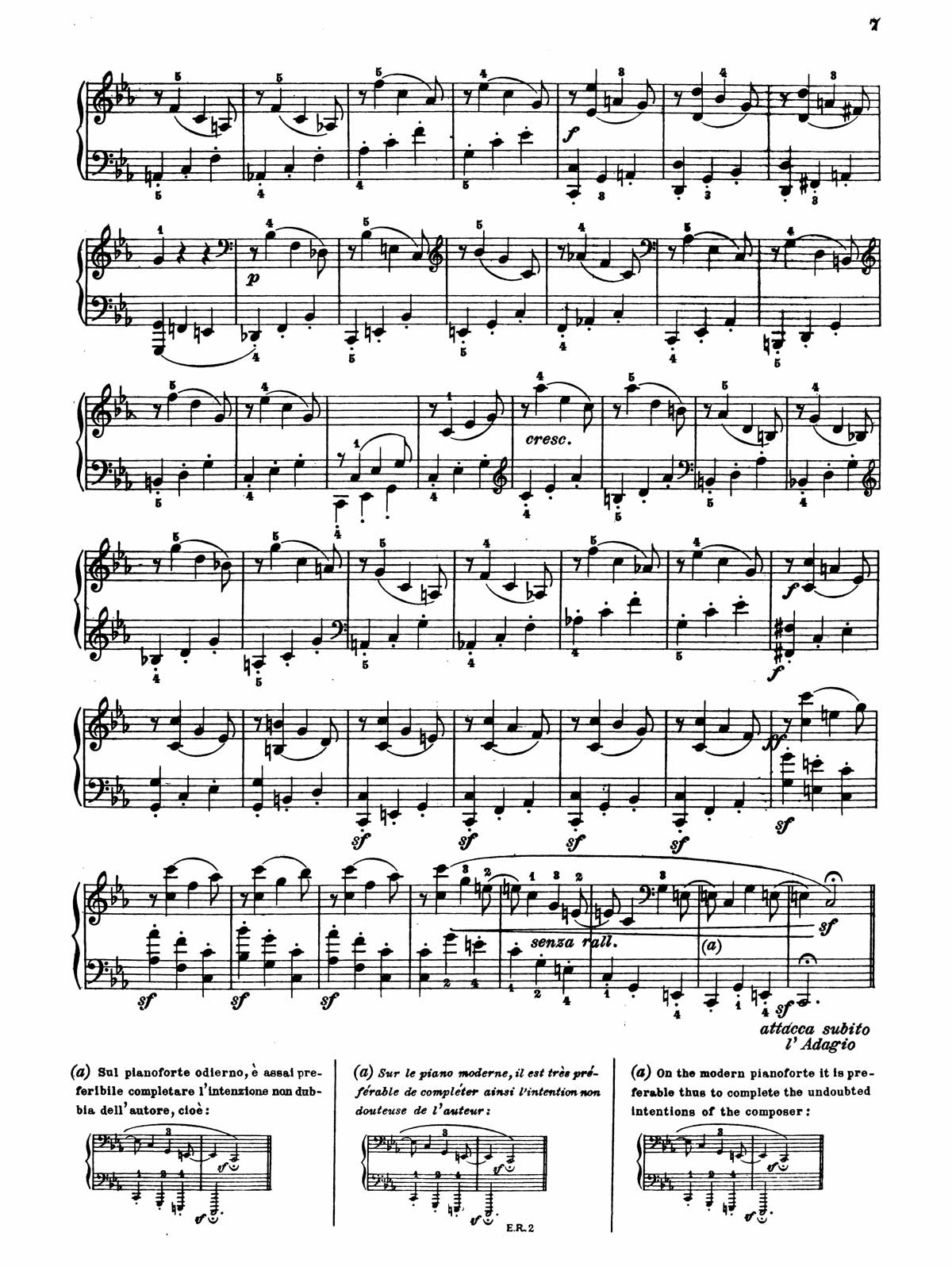

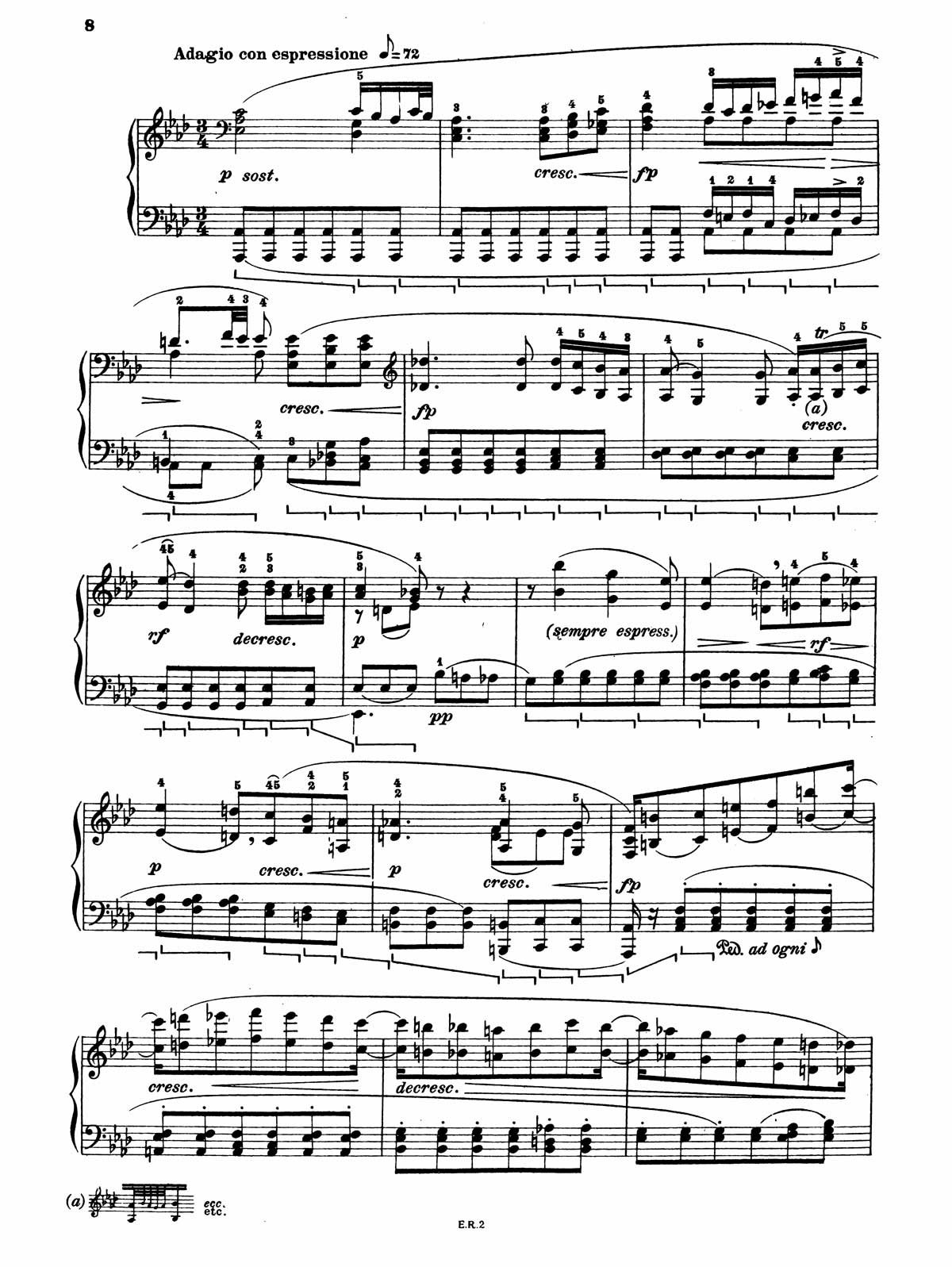

>Third Movement: A flat mayor | Adagio con espressione | 3/4 | ABA, cadenza

Structure

Each ABA section has eight measures. The last bar of the A final section starts the cadenza, which is written within two additional bars.

Measures 8 to 16

The half cadence at the end of the first section is maintained so that section B is in the dominant, E♭ major. A connecting line in syncopated octaves provides a climactic moment in bars 13 to 16.

Measures 24 to 26

The cadence features a rapid ascending scale followed by a trill written in hundred twenty-eighth and sixty-fourth notes. A dominant seventh chord in the opening key of the sonata, E♭ major, is accompanied by a fermata, a cadence written in sixteenth notes, and a final fermata. Then Attaca subito l’Allegro vivace.

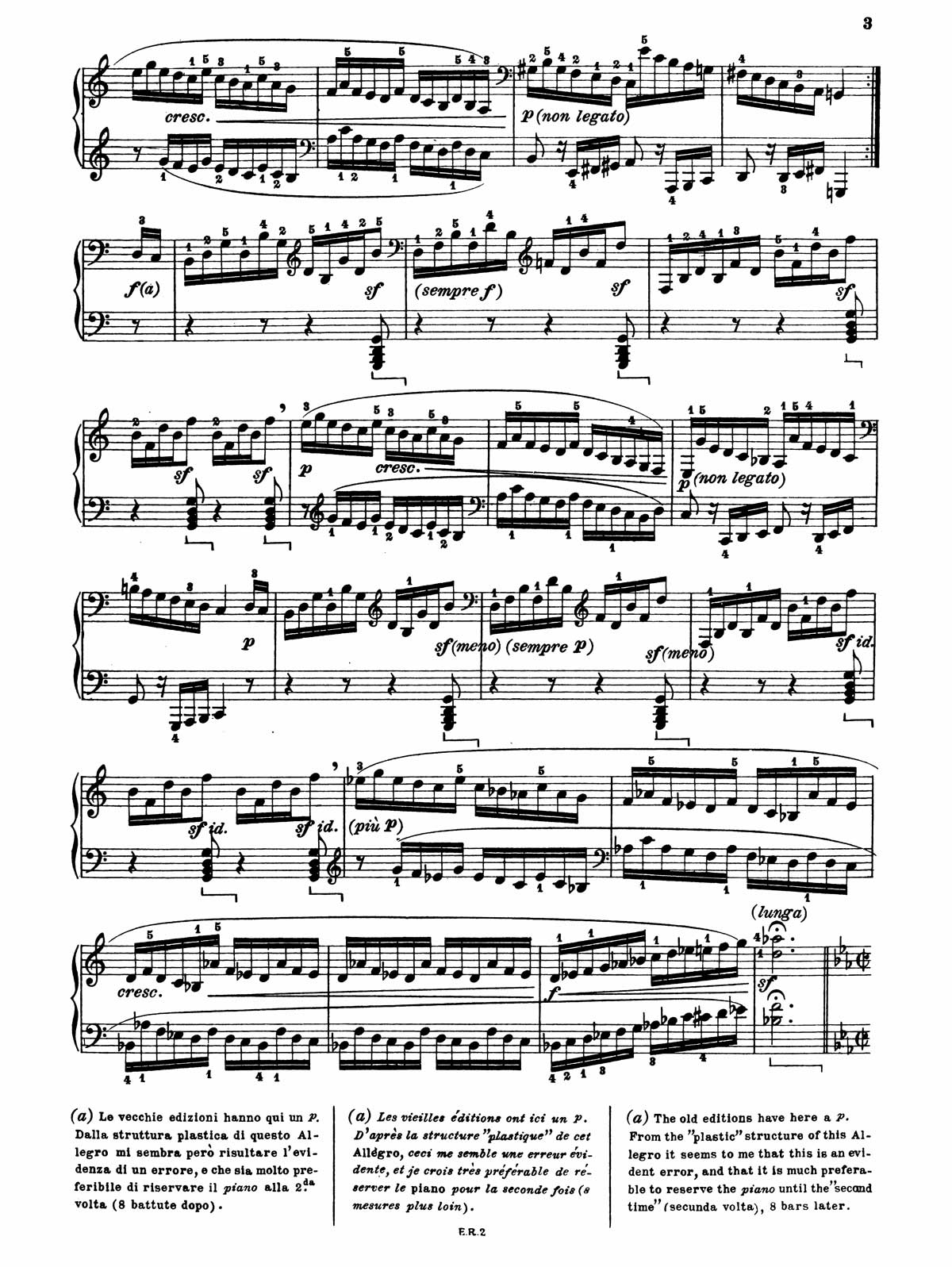

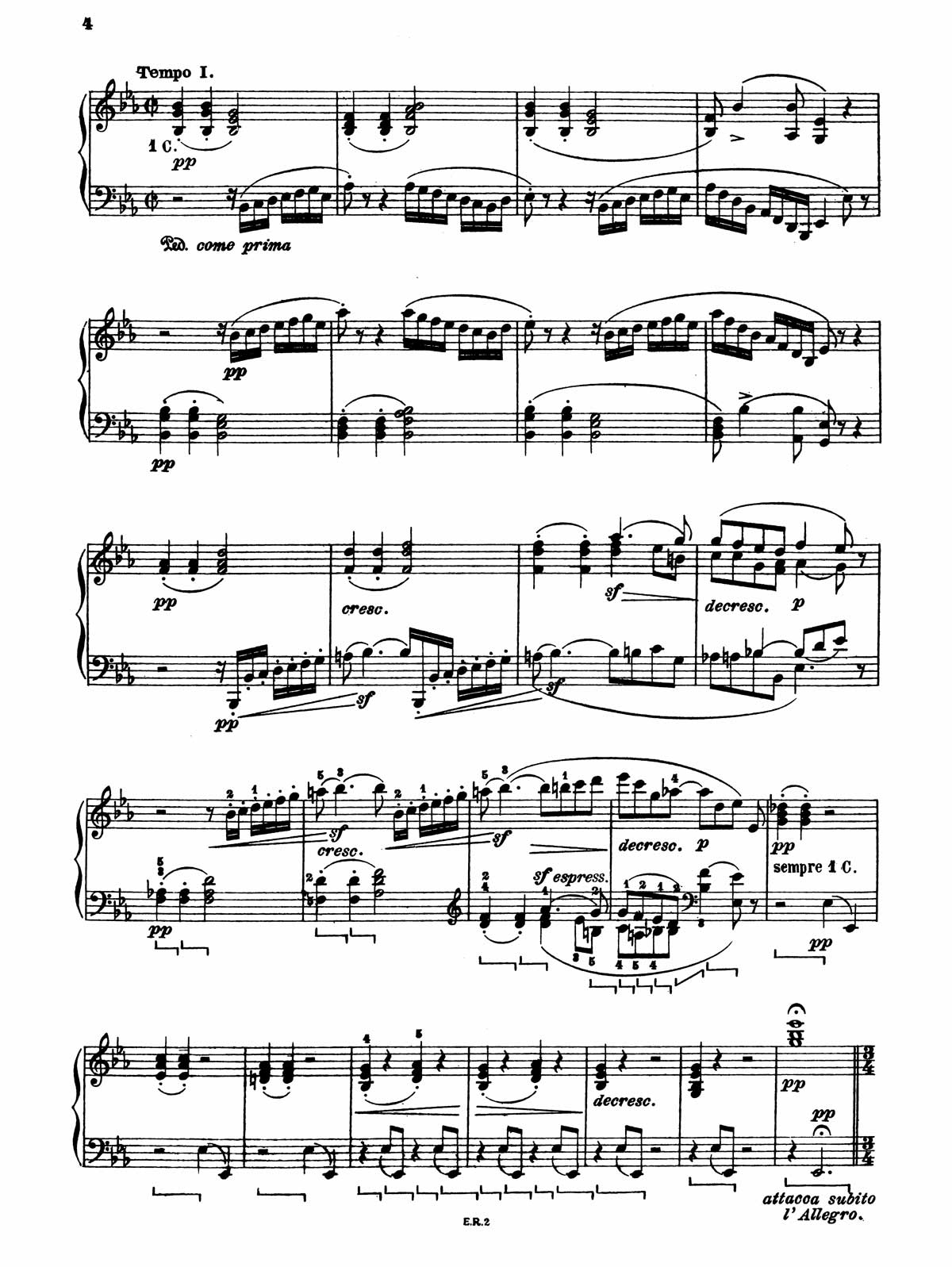

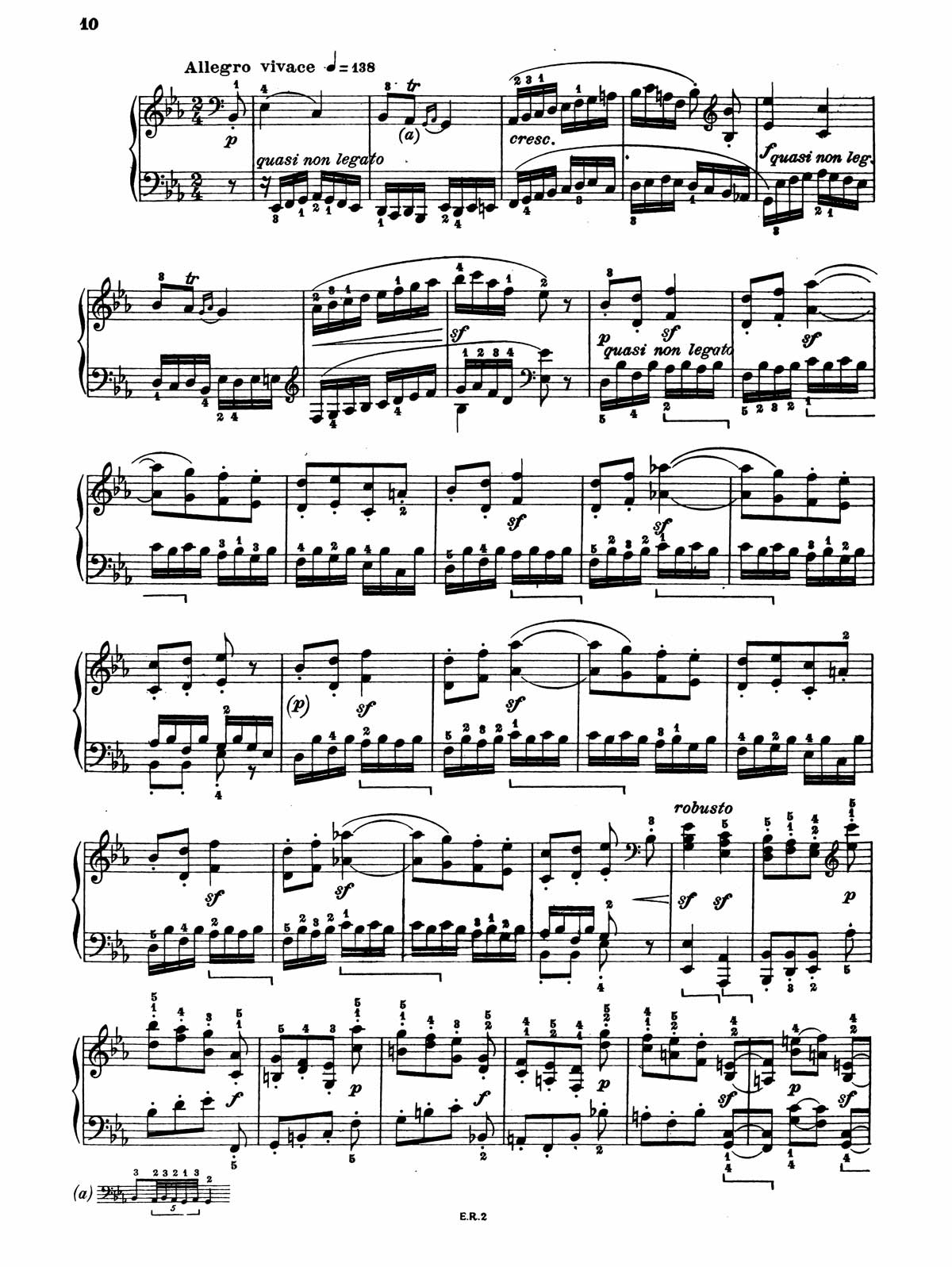

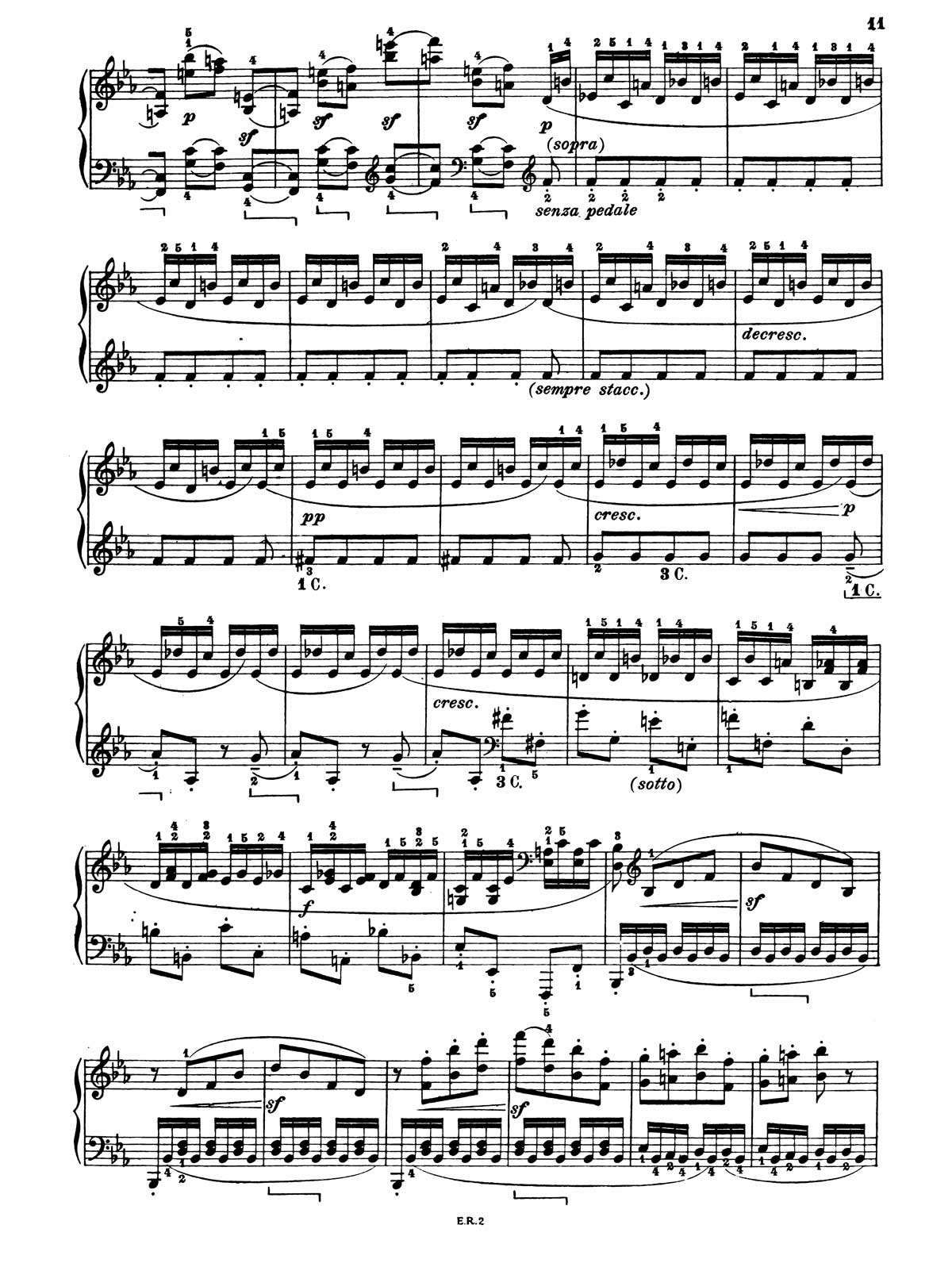

Fourth Movement: E flat major | Allegro vivace | 2/4 | ABACAB | third movement | Coda

Structure

The two B sections are in the dominant and tonic respectively, and the C section is a development of the A section. Thus, the structure of the movement would be classified as a sonata allegro were it not for the return of A between B and C.

Analysis of the written parts

The return of the third movement theme is no longer in A♭ major, but rather in E♭ major, the opening key of the sonata. Curiously, it is accompanied by the Tempo I mark. This marking has led to speculation that the A♭ section, here referred to as the third movement, should be regarded as an introduction to the final movement rather than a separate movement, thus compromising the perception that the sonata is truly cyclical. This perception could be considered as an early example of the procedures used in the later sonatas; 28, 29 and 30, where the last movements have introductions, and in the case of 28, an introduction taken from an earlier work. However, in the case of considering the work as a four-movement one with a cyclical return it is supported by the attaca at the end of the A♭ section, a direction seen between each of the previous movements as well as pitch changes. The section ends with another written cadence marked in presto.