Composed in 1822.

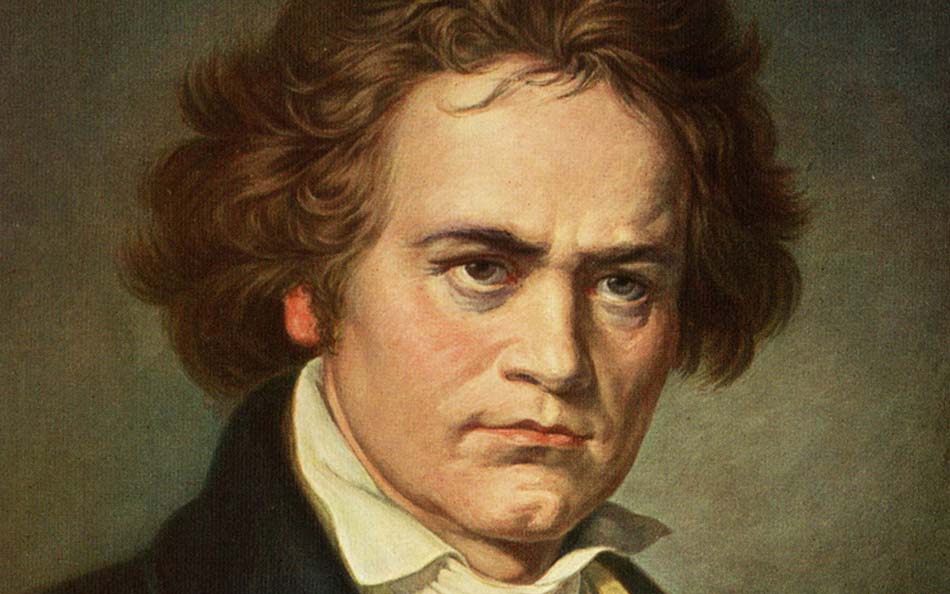

"The genie is made up of 2% talent and 98% constant perseverance." –L. V. Beethoven.

Info and RegistrationBeethoven's latest sonata is often identified as one of the most powerful and transcendent works of piano literature, but if anything, that description understates how incredible this work is. Like all of Beethoven's late sonatas, Op. 111 features a lot of contrapuntal writing in both movements, and a very compressed first movement. But what makes this sonata very different from the rest is the use of polarity, which contrasts between 2 extremes. At the broadest level, you see that this work represents the structure of the sonata, which, unusually for Beethoven, has only two movements; the first irregular and tremendously threatening, the second rarefied, spiritual, generous, sometimes ecstatic. You can also see this game in the contrast between the first and second themes of the first movement; the first theme is tense and angular, almost orchestral, while the second sounds totally improvised. There is also the use of sonic distance in this sonata; In the first movement, the two hands often play parallel passages two or more octaves apart, in addition, there are also passages in thirteen bars and the like, and in the Arietta there are passages where both hands play in the keyboard ends.

The intro, which seems disconnected from the rest of the sonata, is built around a sequence of diminished seventh chords that are repeated at multiple points in the first movement, and particularly dramatically at the end of the development. The astonishing Arietta has an absorbed and highly static theme that comes to life from the increasing rhythmic subdivision to which it is subjected, until it explodes with joy in a particularly famous variation. And then there are the hair-raising trills in the Coda, which introduce the only real tonal diversity into the movement, and the warmth and cuteness of the last two variations, which sneaked in behind the coda.

Beethoven endured a prolonged period of illness between 1821 and 1822. There are no conversation books for a period of approximately nine months. A brief notice in the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung dated January 10, 1821, confirms that the composer was recovering from rheumatic fever. Coming out of this period of illness, sonatas no. 31 and 32, but the work was sporadic because his health recovery was intermittent. Beethoven's brother Johann managed the composer's business affairs and was able to negotiate good prices for new scores, thus helping him get out of debt.

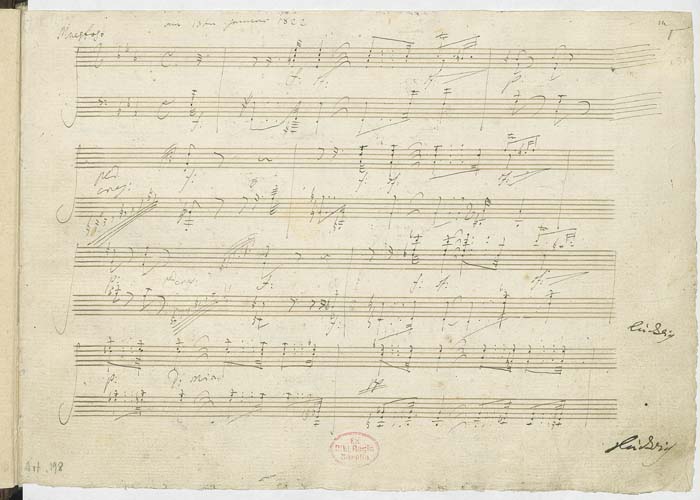

An autograph copy of the first movement of this sonata is housed in the Beethoven-Haus in Bonn. It is dated January 13, 1822 and is believed to be the date the work began, from the completion of the sonata no. 31 which was dated just a few days earlier. Sometime later, a fair copy of the first movement and the first draft of the second were put together, this combination is in the Deutsche Staatsbibliotek in Berlin. Although each of these manuscripts represents a different stage in the composer's creative process, a facsimile of this pairing has been published several times over the years and is frequently found.

This sonata is the third in the trilogy of piano sonatas published by Editorials Schlesinger, first by Moritz in Paris and then from the same plates by Adolf in Berlin. The London publication of Clementi & Co. appeared only a few months later, having been registered at Stationers Hall on April 25, 1823 and presumably traded by Ferdinand Ries. Along with the sonata no. 31, this sonata was originally dedicated to Antonie Brentano, the woman whom scholars believe was the intended recipient of the letter to the Immortal Beloved found among the belongings of Beethoven. The London edition bears this dedication. Despite these intentions, the composer wrote to Archduke Rudolf (1788–1831) on July 1, 1823: As Your Imperial Highness seemed to enjoy the sonata in C minor, I thought I shouldn't be too presumptuous if I gave them the surprise of dedicating it to Your Highness.

The two movements of this work are balanced with striking contrasts, incorporating the dramatic and the contemplative, fast and slow tempos, and minor and major keys.

The dotted rhythm of the introduction to the first movement foreshadows the rhythmic figure of the main theme of the second movement.

The introduction features the dotted rhythm associated with the French Overture.

The opening motif dominates most of the exposition, reinforced in various ways. The only respite occurs in bars 50–55, where a more lyrical phrase in A♭ major briefly introduces itself.

The exposition ends with first and second endings.

The development is based on the first theme of the exhibition. It is presented first in G minor with a slight extension. A counterpoint section in bars 76-85 develops almost like a fleeting exposition with a countersubject. This section moves from G minor to C minor and F minor. At bar 86 the texture changes to prominent chords in the right hand indicating the first three notes of the main motif, accompanied by Sixteenth Note Fragments in the left hand.

The opening theme statement is substantially rewritten, shortening the first thirteen bars to four bars and rearranging the material between the hands.

The lyrical section of the exhibition is now in C major, but is expanded with new material that takes place mainly in F minor.

The final cadence of the recapitulation is prolonged to lead into a coda, which introduces lyrical phrases in F minor and ends in half cadences, the latter repeating itself to establish the key of C major, thus creating a link with the key of the second movement. Some listeners may note a striking similarity to the coda of a later work by Frédéric Chopin, the Etude op. 10, no. 12 Revolutionary.

Each segment is eight measures long, each marked to be repeated, each with a first and second ending.

The use of shorter note values, often called rhythmic crescendo, begins with the introduction of sixteenth notes. Repeat marks are also preserved as trailing first and second.

Time signature change to 6/16.

The last variation on the crescendo rhythmic sequence uses the notes 1/32 1/64, again marked L’istesso tempo and a new beat of 12/32.

This is a double variation in which the repetition of each part is written and is a variation in itself.

This interlude is divided into three parts.

This variation runs without repeats, the theme in the upper voice of the right hand, which also plays an inner voice in sixteenth notes. The left hand provides harmonic support with broken chords at 1/32 notes.

An extension of the figuration of variation five continues to announce fragments of the theme with increasing tension.

The trill is reinstated in a high register of the keyboard. The right hand plays both the extended trills and the first half of the theme, the left hand providing tremolo accompaniment. This variation is one of the best representations of the composer's ability to create momentous moments.

A scalar passage in sixteenth notes in both hands leads to a three-bar reference to the opening fragment of the theme, the movement ending in silence.

Sonata in two movements.