Composed between 1801 and published in 1802. Popularly known as "Moonlight" (from German: Mondscheinsonate). Although in reality the first movement is a funeral march.

Epigraph of the first edition: Sonata Quasi una Fantasia per il Clavicembalo o Piano-forte composta e dedicata alla Damigella Contessa Giulietta Guicciardi da Luigi van Beethoven, Opera 27 No. 2. In Vienna presso Gio. Cappi Sulla Piazza di St. Michele No. 5.

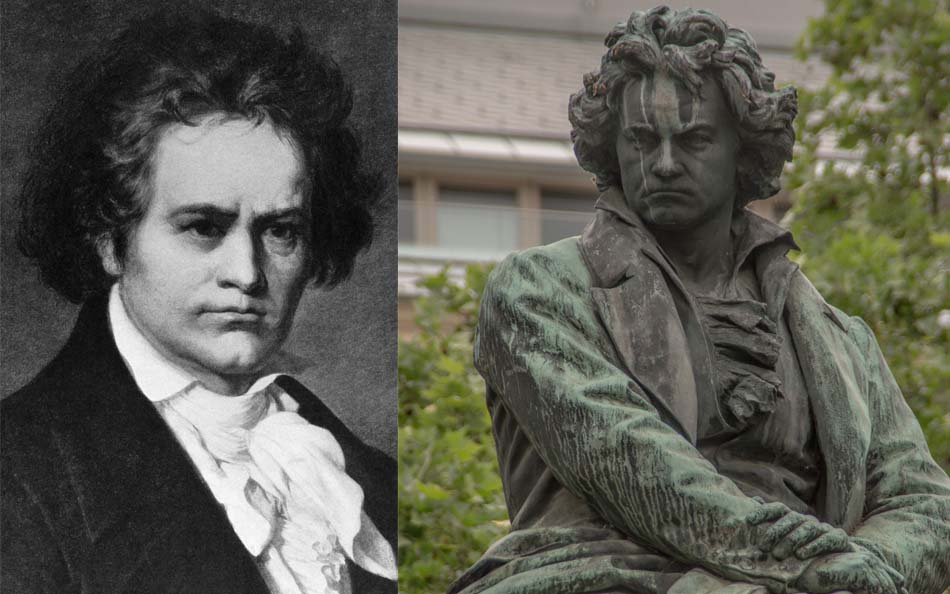

The damigella or young lady to whom the dedication referred was his student, the 17-year-old Countess Giulietta Guicciardi1 and with whom he was said to be in love. She was the daughter of Count Guicciardi, a Triestine character who in the spring of 1800 had been transferred to Vienna as an advisor to the Bohemian Chancellery. The family was related to the Brunswick, close friends of Beethoven, and the artist soon counted Giulietta among his aristocratic disciples, not accepting any remuneration for the lessons in which he was very demanding as a teacher. In those days the musician was approaching thirty years old. After some time, the teacher-student relationships developed into a warmer affection. This can be verified in his correspondence, since after a very melancholic letter written to Wegeler, the teacher addressed him another in which he said: Now I live happier. You will never be able to imagine the life so lonely and sad that I have lived in recent times ... This change is the work of an affectionate, a magical girl who loves me and whom I love. You can also read later : After two years I have again enjoyed a few moments of happiness and for the first time I think that marriage could make me happy, but unfortunately it is not my position and I cannot think of getting married.

In Giulietta's family there was opposition to her love affairs, and this seventeen-year-old girl with a weak or fickle will, very shortly afterwards, married Count Gallenberg, who was an amateur musician who wrote rather mediocre ballets. The rupture between Giulietta and Beethoven occurred immediately after the sonata was published, and the great artist bitterly wept over his disappointment.

The nickname Moonlight would become popular after the death of Beethoven, arising from a comparison that the German poet and music critic Ludwig Rellstab made between the first movement of the work and the Moonlight of Lake Lucerne.

"The genie is made up of 2% talent and 98% constant perseverance." –L. V. Beethoven.

Info and RegistrationThe Moonlight Sonata by Beethoven (which really should be known as the Second Fantasy Sonata) is probably the most popular part of Great World Music, and for good reason. His peculiar brand of expressive and imaginative power is unrivaled in piano literature. The first movement is one of those rare things that, like Bach, is almost totally insensitive to all kinds of interpretive freedom, depending on how you play it it can sound funereal, melancholic, lyrical or tragic.

Interpretive complexities abound in the first movement; Should the polyrhythm of sixteenth note against triplet be dealt with literally? Should the pedal be held down constantly as Beethoven indicates? Half pedal? Third pedal? Delayed Harmonic Shift Pedal? God forbid, the sostenuto pedal? Should we play at the indicated tempo, on the cutoff time, so that it goes almost twice as fast as some performances today, and certainly much faster than listeners are used to? And of course, there is the fact that the first movement is not really in sonata form, technically it is, but I can't imagine people actually hearing it as sonata form, and it develops more like a single fantasy melody. on a really massive scale.

The first movement actually in a funeral march. Touched and thought that way, everything makes sense. Let's just look closely at the beginning; the sustained arpeggios, the slow bass and up the notes that mark the march: G# 3/4 beat, G# 1/4 beat, again G#. What does it sound like? That's right, to a funeral march!

On the contrary, this first movement loses a lot of meaning if we want to force to sound like a romantic dinner with the light of the full moon . His execution becomes meaningless. Try it like a funeral march and you will see the difference.

The second move seems pretty conventional, but there's actually a lot of ironic joy with the ambiguities about where exactly the implicit rhythmic accents should fall, and even possible crossover rhythms in the trio. In any case, it is a sweet piece of the sonata, whose monomaniacal use of repeated cells of music manages to convey a kind of soft humor. Liszt called it a flower between two abysses.

The last movement is one of the miracles of piano literature; it vibrates in an almost perpetual state of climax, but rarely does its dynamics rise to a fortissimo. It is quite obvious to note that it is the main part of the sonata; Again, it is worth noting that Beethoven gradually shifted the weight of his sonatas from front to back. Your second thematic group is richly loaded with wonderful ideas. Most of the power of this move comes from its pulsing and insistent rhythm, there's a reason so many people enjoy technical metal like this; clever use of contrasts, almost ubiquitous vibrant sixteenth notes, and truly dramatic Neapolitan harmony - you could teach quite a few composition lessons using it as a model, but the bottom line is that it's amazing to listen to and quite addictive.

This work is dedicated to Countess Giulietta Guicchiardi. In an early biography of the composer, Anton Felix Schindler claimed that she was the subject of the famous Immortal Beloved love letter found among the composer's memorabilia, but later research discredited this claim. The well-known Moonlight nickname probably came from an account written in 1832 after Beethoven's death by the poet and musician Heinrich Friedrich Rellstab (1799–1860). He wrote of the first movement which was a ship passing through the wild landscape of Lake Lucerne in the moonlight. The autograph of this work survives except for the first and last pages.

The composer joins the first and second movements with the indication attaca subito il seguente, but there is no such indication between the second and third movements. As in the first sonata of the set, the longest movement is the last, rather than the first. Still, the celebrated first movement is prescient in that it sustains a single mood at all times, making emotional effect more important than structural clarity, an aesthetic associated with 19th-century Romanticism.

The first and third movements are both based on a broken triad in C♯ minor. Both highlight the fifth of the scale, g♯, using that tone in the first movement as the opening note of the first theme, the third movement featuring arpeggios culminating in chords on that note, g♯, at the top. Although the second movement, in D♭ major, opens with a dominant phrase, it also ends on the fifth of the scale.

The first and third movements have the same melodic phrases. The developments of the first and third movements focus on F♯ minor

The underlying sonata-allegro pattern unfolds with themes made up of fragments and unusual tonal relationships. The presentational structure seems less important than the mood set by the constant figuration of the triplet throughout the tour and the pedal prompts.

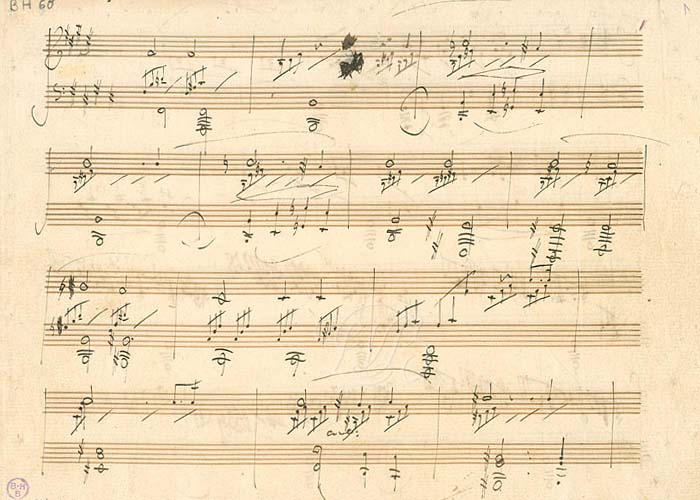

The triplet figure of the right hand is established in this introduction.

The first theme phrase is announced twice, the first opening in C♯ minor and modulated to E major, the second opening in E minor and modulating to B minor.

The second theme phrase is also announced twice, opening both times with a B major sonority that seems to function as an E minor unresolved dominant. The second phrase expands to close the exposition with a F♯ minor cadence.

The opening theme starts in F♯ minor.

A fragment of three notes is presented, possibly derived from the form of the second thematic fragment of the exhibition.

Broken chords, diminished seventh and tonic are displayed.

A re-transition presents a melodic fragment with the same rhythm as the second theme of the exhibition. Some details of this passage have generated controversy, since the derivation in bar 37 is puzzling, and the length of the phrases in 37, 38 and 39 seems inconsistent.

The second theme fragment opens in C♯ major. That seems to work like an F♯ minor unresolved dominant, but it moves to the start key when the section ends.

The coda puts the first theme in the left hand and brings the movement to a calm and smooth ending.

This movement is another example of the composer using a minuet and trio pattern without designating it in writing as a minuet and trio, or a scherzo. Similar procedures occur in Sonata 4, 3rd movement; Sonata 6, 2nd movement; Sonata 9, second movement; Sonata 13, second movement; Sonata 28, second movement, marked march; and Sonata 31, second movement.

The composer orders that this section not be repeated, because the repetition is written, the first eight varying the measures as they are repeated.

The trio section, also in D♭, features syncopated octaves in the right hand.

The ascending arpeggio figure in C♯ minor culminates in two right-hand chords assisted by staccato markings and a pedal indication. These marks are consistent for this step throughout the movement.

The second thematic area is in the dominant minor, g♯ minor, a relationship that exists in other Beethoven sonatas in minor keys; Sonata no. 1, 4th movement, sonata no. 17, first and third movements, sonata no. 23, third movement and sonata no. 27, first movement.

The first theme opens in C♯ major, a harmony that works as a dominant in F♯ minor.

The second theme is presented in F♯ minor and E minor and then extended to reach the dominant of the opening key, C♯ minor.

The retransition builds on a dominant pedal, descending in staccato chords that lead to a passage of fragmented segments related to the closing section of the exposition in bars 94–99. Articulation in bars 91-93 is often compared to that in bar 96 in the autograph, because this passage may be an example of the composer's distinction between accent and period. In this example, the dot at bar 96 is combined with a slur, creating a portato note. As interesting as this passage is, such a comparison has not led to a clear resolution of the general problem of deciphering which marks are dots and which are accents in Beethoven's autographs.

All the material is presented in the recapitulation, although the first theme is truncated. The second theme is in the opening key, C♯ minor. An unexpected modulation to F♯ minor in bars 158-159 paves the way for the coda, the longest and most dramatic modulation in sonatas 1-14.

A statement of the first theme in F♯ minor is interrupted by two diminished seventh arpeggios, each assisted by a fermata. The sensitivity of Beethoven in the use of the pedal highlights the color. The autograph indicates with sirdina in bars 163 to 164, but senza sordina in bars 165 to 166. This differentiation does not appear in the first edition or in many later editions.

The second theme develops in C♯ minor and is extended with a cadence that culminates in a dominant ninth chord and fermata. A cadence written in small notes leads to two full bars marked in Adagio.

A final recapitulation of the closing theme is followed by forte arpeggios and closing fortissimo chords to bring this sonata to a brilliant finale.